The First Punic War (264 to 241 BC) ended with a Carthaginian defeat, leaving the Roman Republic not only the major power in Europe, but across the entire Mediterranean. Carthage was battered and broken, militarily and financially, with Rome adding insult to injury by imposing crippling treaty agreements, trade penalties, and military sanctions. Not unlike Germany after WWI, Carthage became bitter in its defeat, rebuilding itself with the hopes of revenge against the unfair extent of Rome’s victory.

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the Carthaginians’ response to Rome’s perceived power over the Mediterranean. In the decades since their defeat, Carthage had been preparing armies and funds to help fight the Romans another time. Leading them would be one of the greatest strategic military minds in history; Hannibal. Son of a Carthaginian general who served in the First Punic War, Hannibal grew up having a strong hatred for Rome and vowed to take revenge on what they had done to his people. When the time came for war, Hannibal daringly lead his armies across the Mediterranean Sea and up over the Alps which stood in his way a Italy and the heart of Roman Republic.

The Battle of Cannae took place on August 2nd, 216 BC near the town of Cannae, roughly 150 miles from Rome. Hannibal had delivered crushing defeats to the Romans earlier at Trebia and Trasimene, which had demoralized the Roman army and caused the command over the legions to change 3 times. The Carthaginian army was becoming increasingly outnumbered by their Roman enemies, yet had routed them in every battle that had been fought so far. Coming off his victories, Hannibal captured a large supply depot in Cannae, cutting off the Roman supply lines and forcing them to take action against him.

Tiberius Sempronius Longus and Gaius Flaminius, each generals of the Roman army had failed to stop Hannibal’s advance into Italy. The Roman Consul appointed Gaius Terentius Varro and Lucius Aemilius Paullus to retake Cannae before their supply lines were completely destroyed. Marching to Cannae with a force of 86400 soldiers and cavalry, Varro and Paullus were confident in their ability to defeat Hannibal’s smaller force of 50000 Carthaginians. Varro, the senior commanded, was known to be rash, hot-headed, and had a strong hatred for Hannibal. Despite Hannibal’s perfect track record against the Romans, Varro was certain he would be the one to defeat him, and his large force only increased his hubris.

The first skirmish of the battle occurred outside Cannae, as the Romans were approaching the town. Hannibal had sent a small force to ambush the legionnaires, but they were pushed back and did nothing to deter the Romans. This move however, might be what won Hannibal the battle. By defeating the Carthaginian ambush, Varro and the Roman soldiers gained a large amount of morale and confidence; and for Varro, overconfidence. For the rest of the engagements that happened during the battle, Varro would act recklessly, unstrategically, and underestimate the abilities of Hannibal. Paullus was nervous about further engagements, but was wary to withdraw after their first victory. Whether Hannibal was aware he was using the Romans’ strengths against them is unclear, but the strategic significance of the first encounter cannot be understated.

After two days of staying in their respective camps, the armies of Roman and Carthage met in a full battle on the plains of Cannae. Both armies marched forward in line formation, and as they neared each other, Hannibal stretched out his battle line. The cavalry met parallel to the foot soldiers, with the Carthaginians actually outnumbering their Roman counterparts. For the first phase of the battle, everything proceeded normally, everything going according to Varro’s plan of overcoming Hannibal with superior numbers.

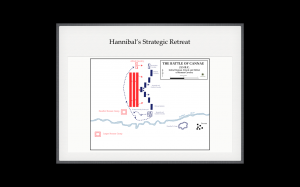

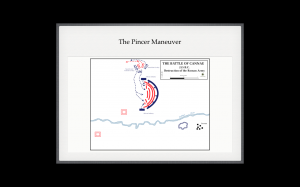

What happened next was all according to Hannibal’s plan though. With his front lines thinned an his battle line longer than the Romans’, Hannibal soon ordered a retreat to his center line, while keeping his flanks advancing. Varro, perceiving his enemy’s front line collapsing, had his troops charge forward, continuing to push back the Carthaginians. After a good deal of retreating, Hannibal stopped his forces, stalling the Roman advance as they crowded towards their front. his allowed for Hannibal’s flanks to sweep inward, creating a semi-circle around the Roman army. The Roman infantry had advance so far that most of their inner lines were unable to see or move freely. Most soldier could not wield their spears they were in such crowded conditions, or draw their swords. The Carthaginians had trapped the Romans in their own mass; their superior numbers meaningless in such a situation.

The cavalry battle was even more of a Carthaginians victory. Their numbers outweighed the Romans’, yet their skill gave them an even greater advantage. Hannibal’s Hispanic and Gallic horsemen were known to be some of the best cavalry in military history, and they annihilated the conservative, inexperienced Roman cavalry. After many cavalry battles had ended, it was normal, almost guaranteed that the victors would ride their horses into the enemy camp, which was presumably unguarded, and loot it; taking treasures, weapons, slaves, and supplies. Hannibal however, wanted to make the most of his advantages, and told his cavalry that after they defeated the Romans, to attack the infantry from behind, completing the circle and surrounding the enemy entirely.

With the cavalry now in the fray, Hannibal had his flanks, consisting of battle-hardened African troops, to turn and march inward. With Hannibal and the Carthaginian infantry at their front, African infantry at their sides, and Gallic cavalry at their rear, the Romans were now encircled in a ring of death. Hannibal successfully executed the first pincer maneuver in military history. The following fighting can only be described as a massacre. The Romans, so packed together, could barely move, much less use their weapons. The Carthaginian army systematically cut down thousands of Roman soldiers, many dying from suffocation as their fellow legionnaires fell on them, crushing them as they tried to dig holes in the ground for air. The killing lasted eight hours, until the night ended the battle.

The Battle of Cannae saw the greatest number of Roman casualties up to that point. If fact, only the Battle of Arausio a hundred years later has a higher casualty count, meaning Cannae is the second largest defeat in Roman history. Casualties number as low as 45000, while some reports say it could be as high as 80000 deaths. For perspective, the Carthaginians had to have killed over 600 Romans a minute for consistency to the lowest figure. Their loss was so great and taken so negatively by the public, that many of the Southern regions of Italy defected from the Roman Republic and joined Hannibal’s cause. Varro was never put in command of a Roman legion again, and Paullus died in the battle. Many of the most excepted figures of casualties (and information on the battle as a whole), are from Roman historians Polybius and Livy. Other have written about the battle, but both Polybius and Livy have the most available records and are considered the most accurate details.

View Hannibal’s Italian Campaign in a larger map.

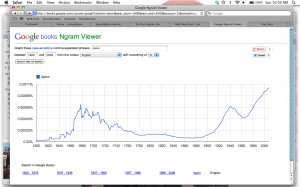

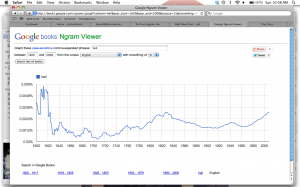

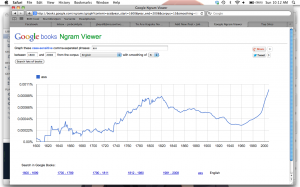

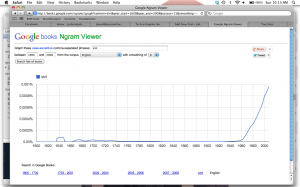

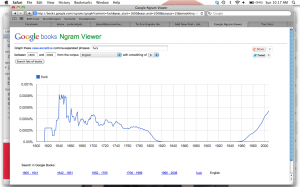

These wordles are of Polybius’ (left) and Livy’s (right) writings on the battle. One difference to notice is the Livy’s records tell a lot more about the political and social aspects surrounding the battle. Words like ‘citizens,’ ‘dictator,’ and ‘gods’ are absent from Polybius’ writings, whose most-used word is ‘battle.’ Of course both have many uses of ‘Hannibal’ and ‘enemy,’ although Livy was known to sympathize with Hannibal in his works, which makes his strong use of ‘enemy’ strange.

Hannibal is known throughout history as an incredibly military commander. Many historians see the cause of his victories to be solely his intellect and strategic planning, yet in the Battle of Cannae, I believe that the Romans have as much to with their defeat as Hannibal does. The first conflict, with the Carthaginian ambush gave Varro and the Roman soldiers too much confidence going into the battle. Rome as a whole had never won a battle against Hannibal, and even being able to deter a small surprise attack would give then false hope in Hannibal’s true abilities. Records and accounts from that time tell us that Varro was reckless and rash. He was of low birth status, and Livy says that he wasn’t well liked by his fellow Consul members. This gives Varro a reason to desire victory as proof of his position and respect of his piers, and why he might have been so ready to defeat Hannibal; throwing his troops up the center of the battle line without concern. Paullus can also be blamed for their failure, as he was in command of the flanks during the battle. While he is considered to be the more level-headed and controlled Roman general, the fact that he let the Carthaginian flanks surround him in such a manner sheds light on his military prowess (or lack thereof). In the end, Varro’s nonexistent tactics and Paullus’ inability to effectively command his troops is just as devastating to the Roman army as Hannibal and the Carthaginians. If Varro had exercised caution and not run headlong into Hannibal’s center, the pincer maneuver would have failed, and the Romans would have been in a much better position even with their cavalry defeated. The Battle of Cannae shows how military advantages can quickly turn into disadvantages if control and intelligence are replaced with stupidity and recklessness.

_____________

Sources:

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/polybius-cannae.asp

http://mcadams.posc.mu.edu/txt/ah/livy/livy22.html